A senior opposition legislator has accused government of systematically eroding local autonomy through increased central directives that contradict Ghana’s constitutional decentralisation framework, calling the trend a structural threat to democracy at the district level.

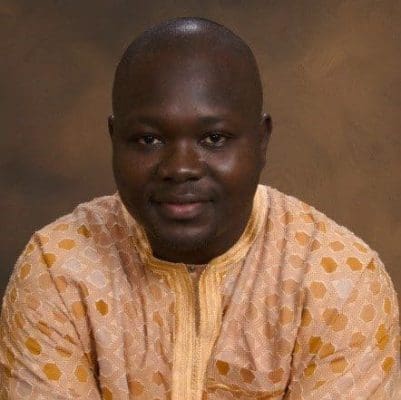

Francis Asenso-Boakye, Ranking Member on Parliament’s Committee on Local Government, Chieftaincy and Religious Affairs, made the charge Wednesday during debate on the Ministry’s 2026 budget allocation of GH¢4.79 billion. The Bantama Member of Parliament (MP) described what he termed “creeping centralisation” as the most worrying development in local governance despite some achievements recorded during 2025.

The legislator argued that assemblies cannot be accountable to their people if they lack discretion and timely resources, pointing to Articles 240 through 252 of the 1992 Constitution and the Local Government Act as establishing clear principles that growing interference from Accra now undermines.

The lawmaker cited multiple systemic problems weakening district governance. Compensation alone consumes 65% of the Ministry’s allocation, leaving limited funds for actual service delivery and infrastructure development. Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) operate with inadequate technical staff and insufficient logistics to execute their mandates effectively. Delays in releasing approved funds compound these challenges, forcing local authorities to operate under constant resource constraints.

However, Asenso-Boakye singled out the increasing practice of central government prescribing operational guidelines and project choices as the most damaging pattern. He described rising central directives as a structural threat to local democracy, arguing that when Accra dictates how districts should allocate resources and which priorities they must pursue, it fundamentally contradicts the constitutional vision of empowered local governance.

The criticism builds on earlier constitutional concerns the legislator raised during November’s budget presentation. At that time, Asenso-Boakye accused government of breaching both the Constitution and Local Governance Act by prescribing utilization guidelines for the District Assemblies Common Fund (DACF) before Parliament approved the distribution formula, a mandatory legal prerequisite under existing law.

He explained that under the law, the Ministry of Local Government, in consultation with the Ministry of Finance, must issue such guidelines only after Parliament approves the DACF Formula. By issuing guidelines beforehand, including earmarking 25% for the flagship 24-hour economy initiative, the legislator argued government was acting outside its legal mandate and effectively removing local discretion over constitutionally guaranteed resources.

The Committee’s recommendations address multiple dimensions of the crisis facing local governance. Strengthening MMDA capacity requires not just additional resources but systematic investment in technical expertise, equipment, and institutional infrastructure that enables effective service delivery. Rebalancing resource allocation means reducing the compensation share to create fiscal space for development spending and operational needs.

Most critically, the Committee called for restoring local autonomy through predictable financing mechanisms and reduced central control over district decision making. This approach recognizes that genuine decentralisation requires not just transferring resources but empowering local authorities to make independent choices reflecting their communities’ distinct priorities and circumstances.

A separate Committee report revealed that persistent shortfall in releases, particularly for Capital Expenditure and Development Partner funds, has stalled several ongoing projects including regional coordinating council office complexes, staff bungalows, and spatial planning facilities. The gap between approved budgets and actual fund releases undermines the Ministry’s ability to deliver on its mandate, creating a cycle where local authorities lack both autonomy and resources.

Ghana’s decentralisation framework emerged from the 1992 Constitution as a cornerstone of the Fourth Republic’s governance philosophy. The constitutional provisions established district assemblies as the highest political and administrative authorities at the local level, deliberately creating structures that would bring government closer to citizens and make it more responsive to community needs.

Over three decades later, the system faces what critics describe as systematic erosion. While the constitutional architecture remains intact on paper, actual practice has drifted toward centralized control that contradicts the original vision. When ministries in Accra dictate how districts must spend their allocations, which projects they should prioritize, and what guidelines they must follow, it transforms supposedly autonomous local authorities into implementation agents for central directives.

The debate reflects broader tensions within Ghana’s governance system between national policy coherence and local self determination. Government officials often justify central guidelines as necessary to ensure resources target priority areas and align with national development objectives. They argue that without coordination from Accra, districts might misallocate funds or pursue projects that don’t serve broader strategic goals.

Local governance advocates counter that this reasoning misses the fundamental point of decentralisation. The constitutional framers deliberately empowered local authorities to make independent decisions precisely because communities differ in their needs, priorities, and circumstances. What makes sense as a priority in coastal Accra may not serve rural communities in the Northern Region. Genuine local democracy requires trusting elected district assemblies to reflect their constituents’ preferences, not imposing uniform prescriptions from the capital.

Despite his sharp criticism, Asenso-Boakye supported approving the GH¢4.79 billion budget allocation. His stance reflects a pragmatic judgment that rejecting the budget would harm local authorities more than government, since districts depend on these funds for basic operations and cannot function without approved allocations regardless of systemic flaws in how resources flow and how much autonomy accompanies them.

The legislator urged government to protect what he called the integrity of Ghana’s decentralisation architecture. Whether authorities in Accra will heed that warning or continue expanding central control remains uncertain. The trajectory over recent years suggests momentum favors centralization, driven by political incentives to demonstrate visible national programs and maintain oversight of resource allocation.

Reversing that trend requires more than rhetorical commitment to decentralisation principles. It demands concrete policy changes that genuinely empower local authorities, predictable financing that arrives on schedule, and willingness from central government to relinquish control over decisions that constitutionally belong at the district level. Without such changes, Ghana’s decentralisation framework risks becoming an empty constitutional promise disconnected from governance reality.