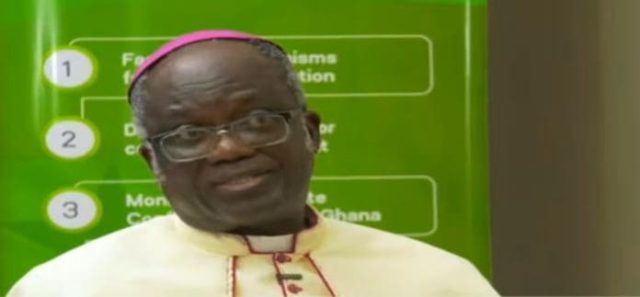

Most Reverend Emmanuel Fianu, Chairman of the National Peace Council, has stated that second cycle mission schools in Ghana provide places of worship for students of other faiths aside Christianity.

Speaking on TV3’s Hot Issues on Sunday, November 30, 2025, Most Reverend Fianu explained that the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed between various religious stakeholders captured such provisions for second cycle mission schools. The MoU was developed by the Conference of Managers of Education Units (COMEU), facilitated by the National Peace Council, validated on April 15, 2024, and endorsed by the Ghana Education Service Director General on April 11, 2025.

The document was signed by 13 missions and religious bodies including the Presbyterian Church of Ghana, Ahmadiyya Mission, African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E) Zion Church, Anglican Church, Assemblies of God Church, Ghana Baptist Convention, Catholic Church, Evangelical Presbyterian Church, Islamic Mission, Methodist Church Ghana, Salvation Army, Garrison Education Unit, and Police Education Unit. The MoU provides a national framework for managing religious diversity in mission schools while preserving their religious ethos.

Most Reverend Fianu’s comments come amid ongoing debate about religious freedom and accommodation in mission schools that receive government assistance. The discussion intensified following a Supreme Court case filed in December 2024 by private legal practitioner Shafic Osman challenging Wesley Girls’ Senior High School over policies allegedly restricting Muslim students from observing key religious practices including wearing the hijab and fasting during Ramadan.

The MoU addresses critical areas of religious practice in mission schools including fasting, dress code, and worship spaces. Under its provisions, students are allowed to fast in accordance with their faith, though permission must be sought by parents or guardians from school authorities with requisite counseling provided before the fasting period commences. Students must however abide by all school rules and regulations during their fast.

On dress code, the MoU stipulates that only prescribed uniforms and mode of dressing of the particular mission based school must be respected, and parents together with their wards must abide by the given directives. Schools are required to make rules and regulations readily available and accessible to the general public, with pupils, students, parents, and guardians taken through orientation on all rules and regulations including fasting, religious place of worship, and dress code.

The framework explicitly states that no student is forced to select or choose a school against their will, and students must be aware of the values of the schools they are choosing and be ready to accept them before opting to attend these schools. This provision aims to ensure informed decision making by parents and students when selecting educational institutions.

The Interior Minister, Muntaka Mohammed Mubarak, launched the MoU at a ceremony in Accra in September 2025, describing it as a milestone in fostering peace, inclusivity, and harmony in educational institutions. He emphasized that the framework was not just about education but about building a nation where differences become a source of strength rather than division.

Deputy Education Minister Clement Apaak highlighted that Ghana’s classrooms are microcosms of the country’s diversity, making them essential places to teach values of inclusivity and tolerance. He pledged the Education Ministry’s full backing to ensure smooth implementation across mission schools. The ministry has committed to working with all stakeholders to create an enabling environment for students of all faiths.

Most Reverend Fianu assured that the National Peace Council would lead a nationwide sensitization programme with support from Regional Education Directors to ensure the guidelines are embraced by all stakeholders. The Council has branches in all 16 regions to facilitate this sensitization effort. He called on educators, parents, and students to join in building schools that serve as sanctuaries of learning and harmony.

The MoU has drawn mixed reactions from religious bodies and advocacy groups. The Ghana Catholic Bishops’ Conference and Christian Council of Ghana issued a statement on November 25, 2025, defending the religious identity of mission schools while acknowledging the MoU’s provisions. They emphasized that financial assistance from the state must not be mistaken for state ownership, nor does it grant any party governmental or religious authority to redefine the character of institutions they established.

The National Muslim Conference of Ghana (NMCG) responded on November 27, 2025, clarifying that Muslim students in government assisted mission schools are not demanding construction of mosques on campuses but only want freedom to pray, fast, and opt out of Christian worship activities. The NMCG described positions limiting rights of minority religious groups in mission schools as unconstitutional and contrary to the signed MoU.

The NMCG referenced the Ghana Education Service (GES) Directive on Religious Tolerance from 2015, which explicitly prohibits forcing Muslim students into Christian worship, denying them the hijab, or preventing them from practicing their faith. The group cited examples of Islamic senior high schools such as T.I. Ahmadiyah in Kumasi, Suhum Islamic Girls Senior High School, and Siddiq Senior High School where Christian female students are not required to wear the hijab, illustrating that religious coexistence is already practiced.

The debate reflects broader tensions about how Ghana balances its long standing mission school traditions with constitutional protections for religious freedom. Mission schools have historically played a central role in Ghana’s educational system, producing generations of leaders while maintaining distinct religious identities tied to their founding missions.

Legal analysts are closely following the Supreme Court case, with some arguing that because Wesley Girls’ Senior High School receives public funding, its policies must align with the Constitution rather than strictly denominational traditions. Others describe the lawsuit as a landmark test of religious accommodation that could shape future policies across public educational institutions.

The Supreme Court has urged all parties to limit discussing and analyzing the case on social media as the matter progresses. The case is expected to provide clarity on the extent to which mission schools receiving government assistance can enforce religious practices while accommodating students of different faiths.

Reverend Thompson Kofi Arboh, National President of COMEU, said the MoU would ensure managers of mission schools enjoy a high level of congeniality in their schools by way of supervision. He stated this would promote teaching and learning and augment the already enviable high academic standards and other co curricular performances that mission schools are known for across Ghana.

The implementation of the MoU represents an attempt to codify practices that balance the religious heritage of mission schools with the rights of students from diverse faith backgrounds. Its success will depend on consistent application across all mission schools and continued dialogue between religious bodies, government authorities, and educational stakeholders.