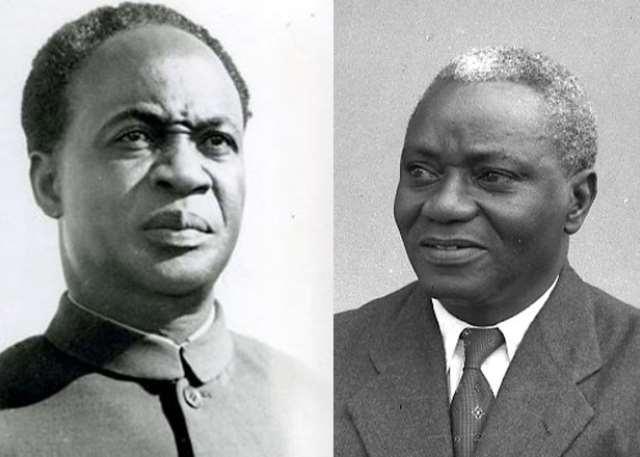

Imagine, just for a moment, that the men whose rivalry shaped Ghana’s first republic could sit together today. Kwame Nkrumah. J. B. Danquah. And those who orchestrated the February 1966 overthrow. Not as ghosts seeking vindication. Not as heroes demanding applause. Just as architects forced to confront what their blueprints became.

I suspect the first thing they would notice is the noise. Ghana has argued about them for over six decades. Founders’ Day debates. Airport naming controversies. Party talking points. Social media skirmishes. Their names have become political instruments rather than historical subjects. And perhaps all of them, even the fiercest rivals, would quietly agree that the argument has sometimes overshadowed the work still unfinished.

Nkrumah would likely speak first about vision. That was always his language. He might say Ghana was meant to be a catalyst, not merely another postcolonial state managing inherited limitations. Industrial ambition. Continental unity. Psychological liberation. He would probably insist those goals remain valid. Yet he might also acknowledge that speed without consensus can fracture trust. Centralization achieved momentum but bred resistance.

Danquah would respond differently. His emphasis was constitutionalism, liberal democracy, rule of law. He warned that concentrated power, even when justified by noble goals, risks silencing the very citizenry independence sought to empower. Looking at Ghana today, he might feel partially vindicated. Competitive elections persist. Courts function. Public debate thrives. Yet he would also have to admit democracy alone has not resolved economic vulnerability or social inequality. Freedom of speech has not automatically delivered freedom from hardship.

Then the conspirators. The officers and officials who justified the coup as national rescue. Their tone might be defensive at first. They would point to economic crisis, political repression, and Cold War anxieties as context for their decision. They might argue they prevented deeper authoritarianism. But they would also confront an uncomfortable legacy. Once military intervention became acceptable, Ghana entered cycles of instability. Coups followed coups. Institutional continuity suffered. Even if their intentions included correction, the method carried long term consequences.

And perhaps here, unexpectedly, the conversation would soften. Because none of them, looking at Ghana now, could claim full victory. The country is stable, respected regionally, democratic by African standards. Yet economic transformation remains incomplete. Youth unemployment persists. Commodity dependence still shapes fiscal health. National unity exists, but political polarization frequently strains it.

Nkrumah might observe that the industrial revolution he imagined did not fully materialize. Danquah might note that democratic practice sometimes drifts into partisan absolutism. The coup planners might concede that force rarely produces lasting legitimacy. Each perspective contains insight. Each also contains blind spots.

What might surprise them most is how their rivalry still structures political identity. Parties claim lineage. Narratives simplify complexity. Citizens sometimes inherit loyalties without interrogating the historical record. The past becomes ammunition rather than instruction.

Yet Ghana itself has matured in ways none of them fully anticipated. Civil society is vocal. Media scrutiny is relentless. Regional diplomacy is active. Cultural confidence is strong. Young entrepreneurs innovate beyond state structures. The Black Star still carries symbolic weight globally. These developments suggest national progress has been collective rather than attributable to any single ideological camp.

If that imagined roundtable continued, I suspect a shared realization would emerge. Nation building was never a single argument to win. It was always a continuing negotiation. Vision without accountability falters. Democracy without developmental urgency stagnates. Stability imposed by force erodes legitimacy. None of these men, individually, solved the equation. Together, unintentionally, they framed it.

The real question for contemporary Ghana is not whether Nkrumah was entirely right, whether Danquah was entirely right, or whether the coup leaders were entirely justified. The question is whether Ghana can extract wisdom from each strand without inheriting their conflicts wholesale.

Because disunity built on historical grievance can become self sustaining. Political actors invoke these figures to mobilize emotion rather than understanding. Citizens sometimes engage history defensively instead of analytically. And the longer that continues, the easier it becomes to blame the past for challenges that demand present solutions.

Perhaps the most productive outcome of that imagined conversation would be silence. Not the silence of suppression, but the pause of reflection. A recognition that history is a foundation, not a battlefield. That development, governance, and unity require synthesis more than rivalry.

Ghana has spent over sixty years arguing about its founders. Maybe the next sixty require building with what all of them, despite their differences, ultimately sought. A confident, prosperous, cohesive nation that no longer needs their quarrels to define its future.