The scars left by British colonialism are deeply etched across continents, from the decimation of Indian resources to the transatlantic slave trade that enslaved millions of Africans.

For Ghana, a nation that was once central to the British Empire’s profiteering machine, the impacts are as relevant today as they were centuries ago.

However, the British government remains reluctant to issue reparations or even a formal apology, a decision recently underscored by the UK Prime Minister ahead of the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM).

This decision disregards the immense suffering and the ripple effects of the slave trade, particularly in African nations like Ghana, which endured the brunt of British imperial ambitions.

For Ghanaians, this silence from the former colonial power is a harsh reminder of unacknowledged history and a legacy of exploitation that continues to shape lives today.

In an era when historical injustices are increasingly scrutinized, many wonder how much longer Britain can withhold recognition of its colonial crimes.

British involvement in the transatlantic slave trade began in 1562, driven by the lucrative economic opportunities offered by a “triangular trade” between Europe, Africa, and the Americas.

By the 18th century, Britain had solidified itself as the world’s largest slave-trading nation, with the financial powerhouse of London serving as the heart of the system.

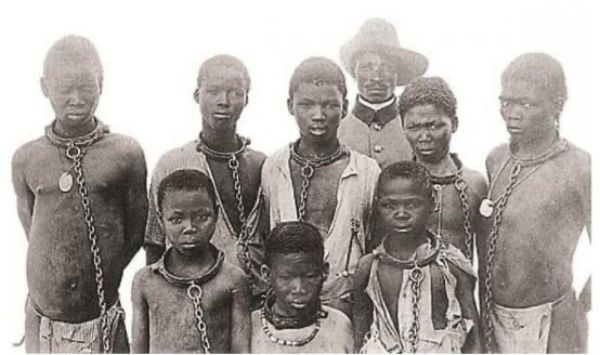

Ships from Liverpool, Bristol, and London dominated the transatlantic routes, trading enslaved Africans as commodities to fuel the empire’s growth.

This trade had catastrophic consequences for African societies, tearing apart communities and families while simultaneously building the foundation of the British Empire’s prosperity.

Britain’s economic success was, in large part, derived from the exploitation of millions trafficked to the Americas under inhumane conditions, suffering unimaginable horrors both at sea and on land.

Among the many African regions affected by European colonialism, Ghana stood as a key site for British exploitation.

Known as the “Gold Coast” due to its rich deposits of precious metals, Ghana was targeted by Europeans, who named its territories based on their economic interests.

The Gulf of Guinea region, comprising Ghana and other neighboring areas, was a vital asset in Britain’s imperial portfolio, not only for its resources but also for the human lives it could exploit.

For enslaved Africans, Ghana was often their final glimpse of home before the treacherous journey across the Atlantic.

This tragic history was later countered by Ghana’s role in igniting the African independence movement.

On March 6, 1957, Ghana became the first sub-Saharan African nation to break free from Western colonial rule, with Kwame Nkrumah proclaiming, “our independence is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of the African continent.”

Ghana’s struggle was not merely for itself but represented the aspirations of the entire continent.

This movement resonated across Africa, fostering unity and inspiring nations to seek independence.

Today, Ghana’s ongoing economic challenges are still deeply rooted in colonial exploitation.

Extractive industries and speculative investments siphon wealth out of the nation, perpetuating an economic model established by colonial powers.

Ghana is far from alone in facing the consequences of British colonial rule. Across the globe, former colonies continue to bear the heavy burden of an empire that prioritized profit over human lives.

In Ireland, one million people starved to death during the Great Famine, as British authorities allowed food to be exported from Ireland despite widespread starvation.

In India, British policies led to the 1943 Bengal famine, resulting in an estimated 3.8 million deaths.

British colonialists plundered India’s wealth, with some economists estimating that more than $68 trillion (in today’s terms) was extracted from the subcontinent.

In Australia, colonial authorities enacted brutal policies, including land theft, massacres, and the abduction of Indigenous children, erasing cultures and communities.

In Britain’s African colonies, violent suppression was a common tool to maintain control.

These histories showcase a pattern of cruelty and exploitation that affected every continent the British Empire touched, leaving a legacy of hardship and inequality that persists today.

The scale of the British Empire’s exploitation has led many to argue that reparations are not only justified but necessary.

A United Nations judge recently estimated that Britain owes approximately £18 trillion ($35 trillion) in reparations for its role in the transatlantic slave trade across 14 nations.

Moreover, Reverend Dr. Michael Banner, Dean of Trinity College, Cambridge, argued that the UK owes the Caribbean alone more than £200 billion for slavery reparations.

Despite such calls, the British government has remained resistant.

The UK Prime Minister’s refusal to offer reparations or even a formal apology speaks volumes, especially as Commonwealth leaders prepare to meet this week.

This resistance contrasts sharply with the approach of Charles III, who, as Prince of Wales, expressed his “personal sorrow” at the suffering caused by slavery during the last CHOGM meeting in Rwanda.

While he has encouraged further research into the monarchy’s links with slavery, symbolic gestures fall far short of the justice that affected nations seek.

Today, 21 African nations are members of the Commonwealth, including Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, and Uganda.

The Commonwealth is an organization that grew out of the British Empire, and its member states share a complex and often painful history.

For Ghana, being part of the Commonwealth brings both opportunities and challenges.

On one hand, the Commonwealth facilitates connections between nations that once suffered under British rule.

On the other, it has yet to address the historical injustices and imbalances that underpin these relationships.

Ghana’s position within the Commonwealth could be pivotal, as its leaders and people push for an honest reckoning with the past.

For the British Empire’s former colonies, the past is not simply history it is a living reality that shapes their present-day economies, social structures, and political systems.

The enduring impacts of the transatlantic slave trade and colonial rule are a stark reminder of the costs that African nations like Ghana paid for Britain’s wealth.

Yet the denial of reparations and a formal apology underscores a persistent injustice. Without acknowledgment, the wounds inflicted by colonialism remain unhealed.

As Ghana and other African nations continue to strive for prosperity and unity, they are also working to overcome the legacies left by colonialism.

Today, the conversation around reparations and acknowledgment is more crucial than ever, especially for younger generations who bear the consequences of an economic system rooted in colonial exploitation.

Ghana’s independence movement was the catalyst for liberation across Africa, but true freedom remains incomplete while the legacy of colonialism endures.

The Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting represents an opportunity for former colonies to confront their shared history and push for justice.

Ghana’s voice, alongside those of other African nations, must be loud and clear: it is time for Britain to acknowledge its past, take responsibility for its actions, and make amends.

Only then can Ghana, along with other nations scarred by the British Empire, begin a journey toward genuine healing and self-determination.

Through unity and resilience, Ghana continues to honor the memory of those who fought for independence and pave the way for a future that acknowledges the truth of its past.

Source: Lazarus Odenge, [email protected]

| Disclaimer: Opinions expressed here are those of the writers and do not reflect those of Peacefmonline.com. Peacefmonline.com accepts no responsibility legal or otherwise for their accuracy of content. Please report any inappropriate content to us, and we will evaluate it as a matter of priority. |

Featured Video