A murder-for-hire case that shocked residents in Markham, Ont., almost 15 years ago is getting the Netflix treatment, highlighting the decade-long ruse Jennifer Pan undertook to please her strict parents — a plot that eventually left one of them dead.

What Jennifer Did is the latest feature-length Netflix documentary to hit the streaming platform (on April 10 in Canada), examining the early years of Jennifer’s life, her forbidden star-crossed-lovers’ romance and her motivation to hire hitmen to kill her parents.

Explained below is the twisted web of lies and deceit that left a mother dead and a family torn apart.

High expectations, tremendous pressure

Born to Vietnamese refugees Huei Hann and Bich Ha Pan, Jennifer felt tremendous pressure to excel in her studies and extracurricular activities and, for years, did just that.

Her parents, the classic example of a Canadian immigrant success story, built a prosperous life for their family and expected their daughter and son, Felix, to expand on their success.

Jennifer was a straight-A student at Mary Ward Catholic Secondary School in Markham and an accomplished piano player, and had her sights set on becoming an Olympic figure skater. By all accounts, she was thriving academically and socially.

Her Olympic dreams were dashed in the eighth grade, when she suffered an injury that sidelined her figure skating career. From there, it was a slow downward spiral.

Jennifer Pan is seen in the promotional poster for Neflix’s ‘What Jennifer Did.’.

Netflix

The self-abuse begins

According to a piece written by one of Jennifer’s schoolmates for Toronto Life magazine, a torn knee ligament was a serious blow to Jennifer’s self-confidence. Her dreams of skating on a national level were dashed and she began self-mutilating by cutting small slices into her forearms.

As her graduation from middle school approached, she fully expected to be named valedictorian and receive a handful of medals for her scholastic efforts. When neither of those things came to fruition she was devastated, but appeared to brush it off and hide behind her “happy mask.”

“A close observer might have noticed that Jennifer seemed off, but I never did,” Karen K. Ho wrote for Toronto Life.

“I discovered later that Jennifer’s friendly, confident persona was a façade, beneath which she was tormented by feelings of inadequacy, self-doubt and shame. When she failed to win first place at skating competitions, she tried to hide her devastation from her parents, not wanting to add worry to their disappointment.”

Over the course of the next two years, her grades began to slip. She went from the top of her class to posting marks in the 70s, at best.

Not wanting to worry and disappoint her parents, she began to lie. Armed with a glue stick and scissors, she altered her report cards, forging them with As to keep up appearances.

Meanwhile, her protective parents kept close tabs on their daughter’s movement through the world. She was forbidden from usual teenage rites of passage like dances and parties. Sleepovers were rare, and when they did happen she would be dropped off late at night and picked up early the next morning.

A forbidden romance

In Grade 11, and well on her path to deceiving her parents, Jennifer began dating Daniel Wong. He was in the grade above and the two played in the school band together.

That year, while on a band trip to Europe, Jennifer suffered an asthma attack. Wong was there to help her through the panic, and Jennifer was grateful for the care and attention he paid to her. They began dating that summer.

Jennifer Pan poses with an award and flowers in an undated image.

Netflix

Wong was, by most accounts, a respectful kid but was dabbling in low-level drug dealing. At one point, as a teen, he was charged with trafficking after police found a considerable amount of marijuana in his car.

Because she knew her parents would never approve of a boyfriend, Jennifer kept the relationship secret. Meanwhile, she was accepted to Ryerson University, now Toronto Metropolitan University, but failed calculus in her senior year and the school withdrew its offer.

The lies deepen

Jennifer never told her parents she wasn’t going to university. She doubled down on the lie and would take transit into downtown Toronto each weekday, holing up at public libraries to take notes from used biology and physics notebooks she thought would be relevant to the sciences program she was supposed to be attending.

She forged documents that said she was receiving a loan for tuition and told her dad she’d won a $3,000 scholarship.

After two years of keeping up her pretend-student charade, she told her dad she’d been accepted into the University of Toronto pharmacology program. She convinced her parents that she should spend three nights a week with a friend in the city to cut down on a gruelling commute — of course, she stayed at Wong’s family home instead.

A still image from Neflix’s ‘What Jennifer Did.’.

Netflix

For another two years, Jennifer kept up the lies. After four years, when it came time to “graduate,” Jennifer faked a perfect transcript and told her parents there weren’t enough tickets for them to attend her convocation.

An unravelling façade

Jennifer’s parents began to notice something was amiss when their daughter began enthusiastically telling them about a new volunteer position at the blood testing lab at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children — a gig that would require late-night shifts on weekends.

Hann, ever-observant and interested in his daughter’s career trajectory, thought it was odd she wasn’t assigned a uniform or key fob to access the hospital.

Concerned, he insisted that he and Bich drive their daughter to the hospital one day. Once she was out of the car, he told his wife to follow Jennifer. Panicked, she ran from her mother and hid out in the ER waiting room until she was certain she had left.

The next day, Hann and Bich placed a call to the friend their daughter claimed to be staying with in the city. The friend admitted that Jennifer wasn’t there. When they confronted their daughter, Jennifer confessed. She told them she had lied about graduating, had lied about volunteering at the hospital and, devastatingly for everyone, she told them she had a boyfriend and had been sleeping over at his house.

Furious and determined to get his daughter back on the right track, Hann took away her phone and laptop. He began checking her phone messages. They forbade her from leaving the house for two weeks.

Jennifer’s anger escalates

Jennifer’s parents eventually granted her some small freedoms. She enrolled in a calculus course to finally finish her high school credits and she was allowed to leave the house for piano lessons.

But Jennifer was still sneaking out to see her boyfriend. One night, her parents found her bed empty and they cracked down on their daughter again, this time demanding that she apply to college and forbidding her from ever seeing Wong again.

Wong, frustrated that Jennifer refused to move out of her parents’ house and tired of having to sneak around, broke up with her and began dating someone else. She was heartbroken and desperate to gain back her relationship, but felt like she had to play by her parents’ rules and worked slowly to regain their trust.

Sometime in the two years after she was caught sleeping over at Wong’s house, Jennifer rekindled her romance with her ex-boyfriend.

Hatching a murder plan

Still being watched closely by her mom and dad, Wong produced a spare phone for Jennifer to communicate with him, away from her parents’ prying eyes.

But the parental scrutiny and lack of privacy was still a major sticking point in their relationship, to the point where Jennifer and Wong also began toying with the idea of murdering her parents and collecting a $500,000 inheritance.

It was with the spare phone that Jennifer asked for a hit to be put on Bich and Han.

Over text, in 2010, Wong introduced his girlfriend to one of his criminal associate friends, Lenford Crawford, whom Jennifer claimed to know only by the name “Homeboy.”

Crawford, over text, told Jennifer he could kill her parents for $10,000. She agreed to the plan.

A harrowing call to police

On Nov. 8, Jennifer called 911, frantically telling the dispatcher that armed gunmen had broken into their home, tied her up, demanded money and shot both her parents.

Bich had been shot multiple times in the head and died instantly. Jennifer’s father, however, was still alive despite bullets to the shoulder and face.

At first, police seemed to buy Jennifer’s story. But, four days later, Hann came out of his coma and told police that his daughter seemed to be familiar and friendly with the gunmen who had entered their home. Remarkably, he remembered everything from the night of the attack, including that his daughter’s hands were not tied behind her back like she had claimed on the 911 call.

Det. Alan Cooke, who worked on the Jennifer Pan case.

Netflix

A series of interviews with police eventually unravelled the truth — at least partially. Jennifer confessed to hiring three hitmen and leaving her home’s front door unlocked, but told police she had hired the men to kill her.

Going through the digital evidence in the case, police uncovered a similar plan, 10 months earlier, that Jennifer abandoned after realizing the person she had paid to kill her folks had ditched her and taken off with the $1,500.

Jennifer was arrested in late November and two months later, in January of 2011, police had enough digital evidence to arrest Wong, Crawford and the two other hitmen, David Mylvaganam and Eric Carty.

All five were charged with first-degree murder, attempted murder and conspiracy to commit murder.

The trial, sentencing and appeal

The trial for Jennifer and the co-accused began in 2014 and stretched for nearly 10 months.

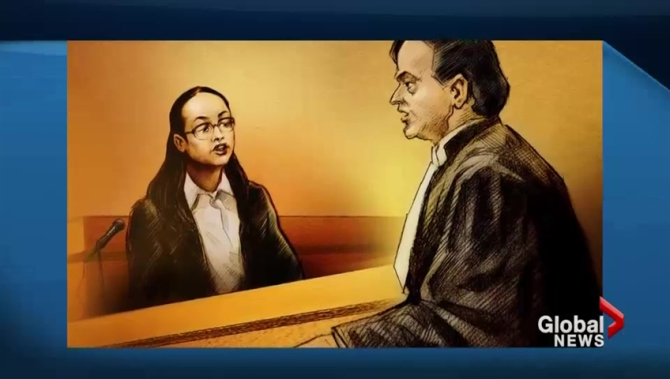

On the stand, she told the jury that she had two plans, but neither involved killing her mother.

The first plan was to have her father shot. When that didn’t work out, she wanted to have herself killed by intruders. She told the jury she thought both plans had been called off.

She also told the court that her life was a fabrication and that she had betrayed her parents at almost every turn for years.

“I was conflicted, I was confused, I was not sure what to do,” she said. “Part of me wanted to come clean. On the other side, I knew coming down, it would bring such shame and embarrassment…. They would be ostracized from the rest of the family.”

A sketch of Jennifer Pan on the stand during her trial .

Global News

When her lawyer asked her why she didn’t just move out of her parents’ house, she said she didn’t want to be without a family.

“I didn’t want them to abandon me. I would be shamed if I moved out and I wasn’t married,” she said.

On Dec. 13, 2014, Jennifer was found guilty of first-degree murder. She was 28 years old at the time.

Three of the co-accused, Crawford, Mylvaganam and Wong, were all found guilty of the same charges for the death of Bich. At sentencing, the judge ordered that all four spend life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years on the murder conviction, and life for attempted murder. The sentences are being served concurrently.

(Carty was not present at the time due to his lawyer falling ill during the trial. Carty died inside a B.C. prison, where he was serving time for an unrelated murder, before he could face trial for Bich’s death.)

Jennifer’s family did not turn up for her sentencing, but in a written statement to the court, Hann said his life had been shattered by his wife’s death and daughter’s crimes.

“I hope my daughter Jennifer thinks about what happened to her family and can become a good, honest person someday,” he wrote.

Jennifer’s legal saga, it seems, is not yet over.

In March of 2023, the Court of Appeal for Ontario ordered new trials for the first-degree murder convictions.

The trial judge erred by suggesting to the jury only two plausible scenarios for the attack — one in which the plan was to murder both parents and another in which the plan was to commit a home invasion and the parents were shot in the course of the robbery, the court said.

But the trial judge should have given the jury second-degree murder and manslaughter as other possible verdicts in Bich’s death, the appeal court said.

The jury could have also doubted there was a plan to kill Pan’s mother, but concluded there was a reasonably foreseeable risk of harming her with the plan to kill Pan’s father, which would lead to a manslaughter conviction, the court wrote.

The Supreme Court of Canada is now in the process of determining if it will review the case.

—

With files from Global News’ Catherine McDonald and The Canadian Press

—

‘What Jennifer Did,’ a documentary by Jenny Popplewell, is available on Netflix on April 10.

—

If you or someone you know is in crisis and needs help, resources are available. In case of an emergency, please call 911 for immediate help.

For a directory of support services in your area, visit the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention.