Chinese schoolchildren are turning to AI bot ChatGPT to slash their homework time — vaulting the country’s “Great Firewall” to write book reports and bone up on their language skills.

With its ability to produce A-grade essays, poems and programming code within seconds, ChatGPT has sparked a global gold rush in artificial intelligence tech.

But it has also prompted concern from teachers, worried over the possibilities for cheating and plagiarism.

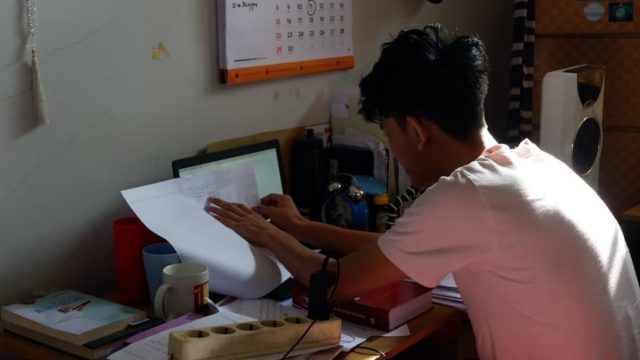

In China, where the service is unavailable without a virtual private network (VPN), over a dozen students told AFP they have used it to write essays, solve science and maths problems, and generate computer code.

Eleven-year-old Esther Chen said ChatGPT has helped to halve the time she studies at home, while her sister Nicole uses it to learn English.

Esther, who attends a competitive school in the southern megacity of Shenzhen, said she used to spend four to five hours every day on homework.

“My mum would stay up late until I finished all my homework and we would fight constantly,” she said. “Now, ChatGPT helps me to do the research quickly.”

Several students told AFP they had bought foreign phone numbers online or used VPNs to bypass restrictions and access ChatGPT.

One retailer allows users to buy a US number for just CNY 5.5 (roughly Rs. 60), while one registered in India costs less than one yuan.

And for those unable to scale the firewall, AI Life on the ubiquitous WeChat app charges CNY 1 (roughly Rs. 11) to ask ChatGPT a question, as do other services.

AI book report

Chinese media last month reported major tech firms, including WeChat’s parent Tencent and rival Ant Group, had been ordered to cut access to ChatGPT on their platforms, and state media blasted it as a tool for spreading “foreign political propaganda”.

But Esther’s mother, Wang Jingjing, said she wasn’t worried.

“We’ve used a VPN for years. The girls are encouraged to read widely from different sources,” she told AFP, adding she is more worried about plagiarism and keeps a close eye on her daughter.

Esther insisted she does not get the chatbot to do the work for her, pointing to a recent assignment in which she needed to finish a book report on the novel “Hold up the Sky” by Liu Cixin, a globally renowned Chinese sci-fi writer.

With a weekly schedule crammed with piano practice, swimming, chess and rhythmic gymnastics, she said she did not have time to finish the book.

Instead, she asked ChatGPT to give her a summary and paragraphs about the main characters and themes, writing the report from that.

‘It’s less pressure’

Students are also using ChatGPT to bypass China’s lucrative English language test prep industry, in which applicants learn thousands of words by rote with expensive tutors ahead of the exams needed to enter colleges in the United States, United Kingdom or Australia.

“I didn’t want to memorise word lists or entire conversations,” Stella Zhang, 17, told AFP.

So instead of spending up to CNY 600 (roughly Rs. 7,000) an hour, she dropped out and now learns through conversations with the chatbot.

“It’s less pressure… It also offers instant feedback on my essays, and I can submit different versions,” she explained.

Thomas Lau, a college admissions counsellor in the eastern city of Suzhou, said more than two dozen students he works with have dropped out of language cramming schools and opted to prepare with ChatGPT.

But the tool has created new problems.

“I run all the personal statements and other application materials written by students through software to detect whether parts of it have been written using AI,” Lau said. “Many fail the test.”

Ban it or embrace it?

A flurry of Chinese tech firms including Baidu, Alibaba and JD.com said they are developing rivals to ChatGPT.

But Beijing is already primed to crack down and said it would soon introduce new rules to govern AI.

While tools to detect whether a text has been written using AI can be accessed in China, schools are also training teachers to ensure academic ethics are upheld.

“The big debate with ChatGPT in classrooms is whether to ban it or embrace it,” said Tim Wallace, a teacher in Beijing.

But with some teachers using the tech themselves, telling students not to is a hard sell.

“Teachers use the tool to generate customised lesson plans within seconds,” he said. “We can’t tell students not to use it while using it ourselves.”