The pizza came on a thick white plastic plate. It was hot. It was decorated with sliced onions, tomatoes, mushrooms and olives. My tongue started bubbling with ecstasy. My thumbs began twiddling with joy.

I tapped my left foot, as the plate finally rested on the concrete bench. I asked for extra plate, so I could slice a hefty portion for my two little boys. Their eyes lit up at the first smell. “This is yummy!” the little one said. “Are they bringing juice for us?” the older brother asked. “I am not sure,” I jokingly said in Dangme, the language we share. The orange juice arrived soon after that. He giggled in excitement.

He slightly nudged his brother to make way for the drinks to be placed next to his plate, which had two slices of the pizza. He pushed the plate toward me, grabbed the orange juice and sipped it. He gave me thumbs up. His brother did same. I tucked into my pizza, sliced a chunk and began to consume it with haste.

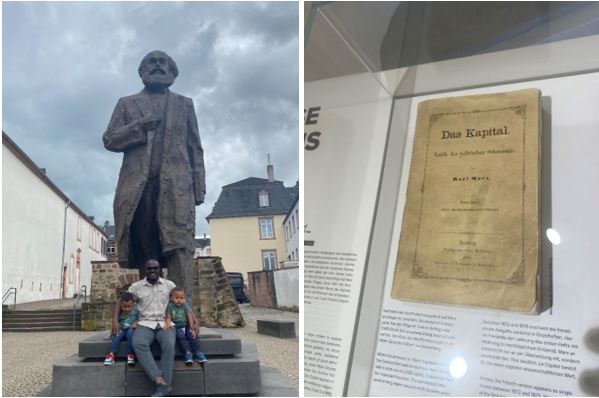

We sat right at the foot of the statue of Karl Marx, the German philosopher, essayist, economist and the man credited for writing strongly about capitalism and its evils. I encouraged my children to eat theirs. I peeled off the last two from each other and buried it in my mouth. I had barely began chewing when the weight of Karl Marx fell on my shoulders. I paused.

I lifted my head and looked at the towering statue. I wanted to leave half a slice at his feet but was not sure if the pigeons or his ghost may consume it. For a man opposed to the obscene opulence of capitalists and their meal taste, I wondered what he would have thought of me eating pizza at his foot. Not sure eating pizza marks me as a capitalist.

But then again, it was just pizza and not sure it constituted part of the things he fought against, and which sent him running for his life; eventually becoming stateless at a point and later settling in London, where he died and was buried. In order not to incur his wrath and for his ghost not to disturb my sleep, I consumed my own pizza.

My little boys yanked a bit of theirs and threw it at the pigeons. Other pigeons began to encroach our space. The boys threw a bit more at them. The thought of Karl Marx wanting pizza kept playing in my head. Maybe I was hallucinating.

A middle-aged woman conducting a city tour appeared through an alleyway leading to the bus lane. About 10 people formed the core of her tour group. I asked the boys for us to make way for them, but she beckoned us to sit. “Kein problem,” she said in German. I suggested to her we were about leaving, in my no so perfect German. She understood me.

However, she politely insisted we go ahead and enjoy our meal. “Danke Frau,” I said to her. She smiled at the boys. I sat through the lecture which was primarily about Karl Marx’s life and his upbringing in the city of Trier. She enumerated the philosopher’s contribution to the economic system, the legacy he left behind, and how his ideas inspired some of Africa’s giants in the struggle for liberation. Karl Marx is arguably the most famous product to have come from the city of Trier.

“Like no other, he analysed the unprecedented dynamics of his own time and criticised growing inequality and exploitation,” the inscription alongside the erected monument read. Two of his prominent books, the ‘Manifesto of the Communist Party’ and ‘The Capital’, have been adopted by the UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register.

Reading through the brief piece about his life, I came across the city’s own concern about how the appropriation of his ideology was sadly abused by dictators, who used that to suppress their own people. “His ideas were abused in the 20th century for the establishment and justification of dictatorships. His cause for thought can still serve today to refine our vision of the problems of modern times,” said the inscription.

Though I was not part of the tour, I raised my hand to contribute when she asked if anyone had a question or clarification. I wanted to know if attempts had been made by the city to get his remains from London to be buried here.

Before she could provide the answer, she asked about my nationality. I said Ghana. Her face lighted up. She said: “You mean Kwame Nkrumah’s Ghana?” I said yes, the one and only ‘Osagyefo’. The rest of the tourists appeared interested, so she gave me some few minutes to speak about Nkrumah and his role in the liberation struggle and how his works continue to inspire generations beyond race.

I realised they wanted more but then the boys were getting tired. As soon as the bus heading toward my direction pulled up, I picked the boys, took my bags and jumped onto it. I hope I represented Nkrumah well, I whispered to myself.

![“It’s hard to say goodbye” – Christian Atsu’s wife composes emotional tribute song for him [Video]](https://ghananewss.com/storage/2023/05/Christian-atsu-and-wife-100x75.jpeg)