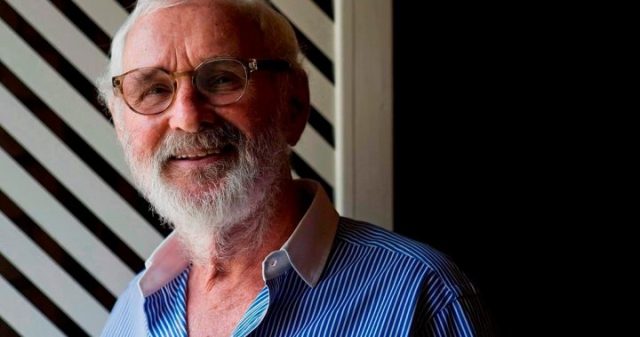

Norman Jewison, the Canadian director of numerous Oscar-recognized titles — including “Moonstruck” and “Fiddler on the Roof” — and a champion of homegrown cinematic talent at the Canadian Film Centre, has died.

A publicist for the Toronto-born filmmaker confirmed that Jewison died peacefully at his home on Saturday. He was 97 years old.

The charming, strong-willed director-producer tackled a wide range of genres throughout his distinguished career, but was particularly drawn to projects that had a social message and explored the human condition.

His five-time Oscar-winning 1967 crime drama “In the Heat of the Night,” for example, was the first of several Jewison films that probed the effects of racism.

It’s an issue that struck Jewison while hitchhiking across the segregated American South as a teen following his one-year service in the Royal Canadian Navy during the Second World War.

“I saw apartheid for the first time,” he said in February 2010 during a panel discussion in Toronto on race relations in cinema.

“I couldn’t understand at 18 … why a country would ask young men to go and fight and die for America and then when they came home, they had to sit at the back of a bus and they couldn’t get a cup of coffee at Woolworth’s.”

Jewison revisited themes of racial tension with his three-time Oscar-nominated “A Soldier’s Story” in 1984, and “The Hurricane” in 1999, which earned Denzel Washington an Oscar nomination for best actor.

IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT, Rod Steiger, director, Norman Jewison, & Sidney Poitier, rehearsing the script, in Belleville, IL, September 23, 1966. Film was released in 1967.

THE HURRICANE, Denzel Washington, director Norman Jewison, on set, 1999. (c) Universal Pictures/ Courtesy: Everett Collection.

His other Oscar-winning or nominated features spanned film genres, with the crime drama “The Thomas Crown Affair,” the musical “Jesus Christ Superstar,” and the Cold War satire “The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming.”

There were also the thrillers “…And Justice for All” and “Agnes of God,” as well as the romantic comedy “Best Friends.”

The beloved romantic comedy “Moonstruck” won Oscars for Cher as best actress and Olympia Dukakis for best actress, as well as screenplay.

Jewison, born in his grandmother’s house in 1926, was raised a Methodist but was often confused for being Jewish because of his surname. He was passionate about performing and storytelling from a young age and obtained a bachelor’s degree in general arts from University of Toronto’s Victoria College in 1949.

After failing to land acting gigs in New York and Hollywood, Jewison drove a taxi and waited on tables in Toronto to support his fledgling career in show business.

His first steady showbiz work came in television, first as a scriptwriter with the BBC in London and then as a writer, director and producer for CBC-TV in Toronto. It was around this time, in 1953, that he wed model Margaret Ann (Dixie) Dixon, with whom he had three children — Michael, Kevin and Jennifer. They remained married until her death in 2004.

Jewison followed up his CBC gig with a directing position at CBS in New York, where he oversaw performers including Harry Belafonte, Jackie Gleason and Judy Garland.

On the suggestion of actor Tony Curtis, Jewison started directing films and got his breakthrough with the lauded 1965 gambling drama “The Cincinnati Kid.”

Many honours followed, including being named companion of the Order of Canada in 1992 and earning the Irving G. Thalberg Award for lifetime achievement from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, in 1999.

Jewison’s name is also immortalized on stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and Canada’s Walk of Fame.

“You don’t see a display of genius like that very often in your life and it’s a direct emanation of the soul of this beautiful man,” David Peterson — Jewison’s friend and U of T chancellor who was also once Ontario premier — said at the Jewison archive launch.

Norman Jewison celebrates after winning the Irving Thalberg Award, in recognition of his consistent high quality of motion picture production, during the 71st Annual Academy Awards Sunday, March 21, 1999, at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion of the Los Angeles Music Center. (AP Photo/Reed Saxon).

Jewison was also a beloved colleague and coach in the eyes of many cinematic heavyweights, who said his directing style could draw out the best in them.

Dukakis, for instance, called him a “master craftsman” and “consummate teacher” during her acceptance speech for her Golden Globe Award for “Moonstruck.”

Many budding homegrown filmmakers regarded Jewison as a mentor during their studies at the Canadian Film Centre, which he founded in 1988.

Jewison also showed his nationalism by shooting several films in Canada and advocating for Canuck culture during many public speaking opportunities.

“The power of our arts is the essence of Canada,” he said in a June 2008 convocation address at what was then called Ryerson University.

“Artists are our most precious commodity because we supply the images and the words through which we see and understand ourselves as a people.”

Despite having homes in several cities around North America, Jewison said he always felt most comfortable on Canadian soil, especially at his farm in Caledon, Ont., northwest of Toronto, where he and his family raised pigs and cattle.

“Most people consider me a Hollywood director but I feel very Canadian. I always have,” he told The Canadian Press in 1979.

“Canadians can be more objective (about the Americans). We’re more like them than anyone else but we’re still outsiders.”

Known for his hearty laugh and feisty confidence, the moviemaker always hesitated to pick a favourite film of his, often saying they were all like his children and all a result of determination, good timing, the right casting and luck.

His biggest piece of advice to budding filmmakers: “Believe in yourself.”

“A lot of it is self-confidence when you get into any of the arts,” Jewison told reporters in September 2008 at the launch of his permanent archive at his alma mater, the University of Toronto.

“All of the arts are difficult because there’s a lot of competition and a lot of people that tell you that you’re not good enough and you’re not special enough and all of those things, so you’ve got to stay at it … and just stay committed.”

![“It’s hard to say goodbye” – Christian Atsu’s wife composes emotional tribute song for him [Video]](https://ghananewss.com/storage/2023/05/Christian-atsu-and-wife-100x75.jpeg)